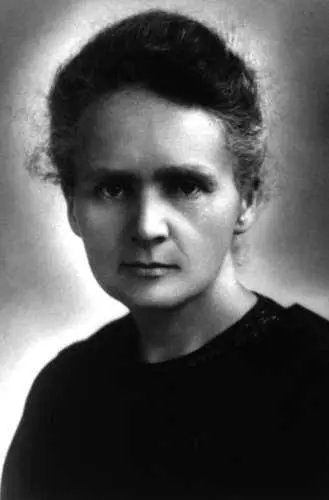

Marie Curie Biography : A Life of Groundbreaking Discovery

Marie Curie Biography : In the annals of scientific history, few names shine as brightly as that of Marie Curie. A pioneer in the field of radioactivity, a two-time Nobel laureate, and a trailblazer for women in science, Curie’s life story is one of perseverance, brilliance, and unwavering dedication to the pursuit of knowledge. From humble beginnings in Russian-occupied Poland to becoming one of the most celebrated scientists of all time, Marie Curie’s journey is nothing short of remarkable.

Early Life and Education

Marie Skłodowska was born on November 7, 1867, in Warsaw, Poland, then part of the Russian Empire. The youngest of five children, she grew up in a family that placed great value on education, despite facing financial hardships and the oppressive policies of the Russian authorities. Her father, Władysław Skłodowski, was a teacher of mathematics and physics, while her mother, Bronisława, ran a prestigious girls’ boarding school until illness forced her to retire.

Young Marie, known to her family as Manya, was a precocious child with an insatiable curiosity about the world around her. She learned to read at the age of four and quickly developed a passion for learning. However, tragedy struck early in her life when her mother died of tuberculosis when Marie was only ten years old. This loss deeply affected the young girl, but it also strengthened her resolve to pursue her studies with even greater determination.

Despite her academic prowess, Marie faced significant obstacles in her pursuit of higher education. The Russian authorities, who controlled Poland at the time, were hostile to intellectual activities among Poles, particularly women. After completing her secondary education with high honors, Marie found herself unable to enroll in a regular university due to her gender.

Undeterred, she and her older sister Bronisława made a pact. They would take turns working to support each other’s education. Marie worked as a governess for several years, sending money to her sister in Paris. When it was finally her turn to study, Marie moved to Paris in 1891 to attend the Sorbonne.

Life in Paris was not easy for the young Polish student. Living in a tiny attic room, Marie often went hungry and cold as she threw herself into her studies with single-minded focus. Despite these hardships, she thrived academically, earning degrees in physics and mathematics. It was during this time that she adopted the French version of her name, Marie, which she would use for the rest of her life.

Meeting Pierre Curie and Early Scientific Career

In 1894, Marie met Pierre Curie, a brilliant physicist who would become her husband and scientific partner. Their relationship began as a meeting of minds, with both recognizing in the other a kindred spirit dedicated to scientific inquiry. Pierre was immediately impressed by Marie’s intelligence and passion for science, and their collaboration soon blossomed into romance.

The couple married in 1895 in a simple civil ceremony. In lieu of a wedding dress, Marie wore a dark blue outfit that would later serve as her lab attire. This practical choice was emblematic of the Curies’ dedication to their work – even on their wedding day, science was never far from their minds.

Marie’s early scientific work focused on the magnetic properties of steel, but it was a discovery by Henri Becquerel in 1896 that would set her on the path to her most famous work. Becquerel had discovered that uranium salts emitted rays that could penetrate solid matter, similar to the recently discovered X-rays. Intrigued by this phenomenon, Marie decided to make it the subject of her doctoral thesis.

The Discovery of Polonium and Radium

Working in a converted shed at the School of Physics and Chemistry in Paris, Marie began a systematic study of uranium rays. She quickly made a groundbreaking discovery: the rays were a property of the uranium atom itself. This was a revolutionary idea at a time when the atom was thought to be indivisible.

But Marie’s most significant breakthrough was yet to come. As she tested various uranium-containing minerals, she found that some were more active than pure uranium. This led her to hypothesize the existence of a new, unknown element that was even more radioactive than uranium. Pierre, excited by his wife’s findings, set aside his own research to join her in this quest.

The Curies’ work was painstaking and physically demanding. They processed tons of pitchblende, a uranium ore, carefully isolating its components through a series of chemical procedures. Their efforts were carried out in primitive conditions, with inadequate facilities and a lack of proper safety measures – the dangers of radiation exposure were not yet understood.

In July 1898, the Curies announced the discovery of a new element, which they named polonium after Marie’s native Poland. A few months later, in December, they announced the discovery of another new element: radium. These discoveries sent shockwaves through the scientific community and would eventually earn the Curies worldwide fame.

The Nobel Prize and Growing Recognition

The Curies’ groundbreaking work did not go unnoticed. In 1903, Marie was awarded her doctorate, becoming the first woman in France to earn a doctoral degree in science. That same year, Marie, Pierre, and Henri Becquerel were awarded the Nobel Prize in Physics for their work on radioactivity.

The Nobel Prize brought the Curies international recognition, but it did little to change their modest lifestyle. They poured most of the prize money back into their research, using it to hire their first lab assistant. Marie, in particular, seemed uninterested in fame or fortune, preferring to focus on her work.

Despite her growing renown, Marie faced ongoing challenges as a woman in science. The French Academy of Sciences refused to elect her to membership, a slight that Pierre protested by refusing his own election until Marie was admitted. (She would eventually be elected, but only after Pierre’s death and after becoming the first person to win two Nobel Prizes.)

Tragedy and Perseverance

In 1906, tragedy struck when Pierre was killed in a street accident, run over by a horse-drawn cart. Marie was devastated by the loss of her husband and scientific partner. However, in keeping with her character, she channeled her grief into her work. She took over Pierre’s position at the Sorbonne, becoming the first woman to teach there.

In her inaugural lecture, Marie paid tribute to her late husband and vowed to continue their work. She threw herself into her research with renewed vigor, working to isolate pure radium and to establish international standards for radioactive emissions.

Despite her personal loss and the demands of single motherhood (the Curies had two daughters, Irène and Eve), Marie’s scientific output remained impressive. In 1911, she was awarded a second Nobel Prize, this time in Chemistry, for her discovery of radium and polonium and her work in isolating radium.

This second Nobel Prize came at a time of personal turmoil for Marie. She had become romantically involved with Paul Langevin, a former student of Pierre’s who was married but separated from his wife. When news of the affair became public, it sparked a scandal in France. Marie faced vicious attacks in the press, with much of the criticism taking on xenophobic and sexist overtones.

The Nobel committee, concerned about the scandal, suggested that Marie not attend the award ceremony. In a display of characteristic determination, Marie refused to bow to this pressure. She attended the ceremony and accepted her prize, asserting that “the prize has been awarded for the discovery of radium and polonium. I believe that there is no connection between my scientific work and the facts of private life.”

World War I and the Petit Curies

When World War I broke out in 1914, Marie Curie saw an opportunity to put her scientific knowledge to practical use. Recognizing the potential of X-ray technology to help treat wounded soldiers, she worked tirelessly to equip ambulances with mobile X-ray units.

These vehicles, which came to be known as “petites Curies,” revolutionized battlefield medicine. They allowed doctors to quickly locate shrapnel and bullets in wounded soldiers, greatly improving their chances of survival. Marie herself drove one of these units to the front lines, often accompanied by her teenage daughter Irène.

In addition to her work with the mobile X-ray units, Marie also trained other women to be X-ray operators. By the end of the war, it’s estimated that more than a million wounded soldiers had been treated with the help of her units.

The Radium Institute and Later Years

After the war, Marie turned her attention to establishing the Radium Institute (now the Curie Institute) in Paris. This institute, dedicated to research in physics, chemistry, and medicine, became a major center for the study of radioactivity.

Marie continued her scientific work well into her sixties, despite growing health problems likely caused by her long-term exposure to radiation. She made several trips to the United States, where she was received with great enthusiasm and was able to secure donations of radium for her research.

In her later years, Marie took great pride in the scientific achievements of her daughter Irène, who followed in her mother’s footsteps and became a noted scientist in her own right. Irène and her husband, Frédéric Joliot, would go on to win the Nobel Prize in Chemistry in 1935 for their discovery of artificial radioactivity.

Marie Curie died on July 4, 1934, at the age of 66, from aplastic anemia, likely caused by her years of exposure to radiation. Even in death, her legacy of scientific discovery continued – her notebooks from the 1890s are still too radioactive to handle without protective equipment.

Scientific Legacy and Impact

Marie Curie’s scientific contributions were revolutionary. Her work on radioactivity fundamentally changed our understanding of matter and energy. The discovery of polonium and radium opened up new fields of research and led to important applications in medicine, particularly in the treatment of cancer.

Curie’s work laid the foundation for much of 20th-century physics and chemistry. Her insights into the nature of radioactivity paved the way for later discoveries in nuclear physics and quantum mechanics. The techniques she developed for isolating radioactive isotopes are still used today.

In medicine, the impact of Curie’s work has been profound. Radium therapy, which she pioneered, became a major tool in the fight against cancer. Although we now use other radioactive elements, the principle behind radiation therapy remains the same as when Curie first proposed it.

Beyond her specific scientific achievements, Curie’s rigorous and meticulous approach to research set new standards in scientific methodology. She insisted on reproducibility in experiments and was known for her careful measurements and detailed record-keeping.

A Pioneer for Women in Science

Perhaps as significant as her scientific contributions was Marie Curie’s role as a trailblazer for women in science. In an era when women were largely excluded from higher education and scientific research, Curie broke barriers at every turn.

She was the first woman to win a Nobel Prize, the first person (and still the only woman) to win two Nobel Prizes, and the first woman to become a professor at the Sorbonne. Her success opened doors for other women in science and challenged prevailing attitudes about women’s intellectual capabilities.

Throughout her career, Curie advocated for women’s access to university education and for recognition of women’s scientific achievements. She mentored many young scientists, both men and women, and took particular pride in supporting aspiring female researchers.

Curie’s example inspired generations of women to pursue careers in science, technology, engineering, and mathematics (STEM) fields. Even today, she remains a powerful symbol of scientific excellence and perseverance in the face of adversity.

Personal Life and Character

Despite her fame, Marie Curie remained a modest and unassuming person throughout her life. She was known for her single-minded focus on her work, often to the exclusion of material comforts or social niceties. Her daughter Eve once described her as “humble with pride which was to make her invulnerable.”

Curie was deeply committed to the idea that scientific knowledge should be freely shared for the benefit of all humanity. She refused to patent the radium-isolation process, believing that it should be open to all researchers. This decision likely cost her a fortune, but it was in keeping with her belief in the importance of scientific openness and collaboration.

In her personal life, Curie was devoted to her family. Her relationship with Pierre was one of deep mutual respect and shared intellectual passion. After his death, she raised their two daughters as a single mother while continuing her demanding scientific work. Both daughters went on to have distinguished careers – Irène in science and Eve as a writer and journalist.

Curie had a love for nature and enjoyed outdoor activities like cycling and swimming. She found solace in the natural world, often taking walks in the countryside to clear her mind and rejuvenate her spirit.

Despite her scientific brilliance, Curie struggled with bouts of depression throughout her life, particularly after Pierre’s death. She coped with these challenges by immersing herself in her work, finding purpose and meaning in scientific discovery.

Cultural Impact and Enduring Legacy

Marie Curie’s influence extends far beyond the realm of science. She has become a cultural icon, a symbol of scientific genius and perseverance against odds. Her life story has been the subject of numerous books, films, and plays, each seeking to capture the essence of this remarkable woman.

In her native Poland, Curie is revered as a national hero. The element that she discovered and named after her homeland, polonium, serves as a permanent reminder of her patriotic feelings. In France, her adopted country, she is equally celebrated, with streets, schools, and research institutions bearing her name.

The Curie name has become synonymous with scientific excellence and integrity. The unit for measuring radioactivity, the curie, was named in honor of Pierre and Marie. The Curie Institute in Paris, which Marie founded, continues to be a leading center for cancer research and treatment.

In recent years, there has been renewed interest in Curie’s life and work, particularly as issues of gender equality in STEM fields have gained prominence. Her story continues to inspire young people, especially girls and women, to pursue careers in science and to persevere in the face of obstacles.

Conclusion Of Marie Curie Biography

Marie Curie’s life was one of extraordinary achievement and unwavering dedication to scientific discovery. From her humble beginnings in Poland to her groundbreaking work in Paris, she overcame numerous obstacles – poverty, prejudice, personal tragedy – to become one of the most influential scientists of all time.

Her discoveries revolutionized our understanding of matter and energy, laid the groundwork for nuclear physics, and opened up new frontiers in medical treatment. But perhaps even more important than her scientific achievements was the example she set. In a world that often doubted women’s intellectual capabilities, Curie proved that scientific genius knows no gender.

Today, more than a century after her most famous discoveries, Marie Curie’s legacy continues to shine brightly. She remains an inspiration to scientists and non-scientists alike, a testament to the power of curiosity, perseverance, and the relentless pursuit of knowledge. In the pantheon of scientific greats, Marie Curie stands as a towering figure – a pioneer, a genius, and a true hero of science.

Check this out for more such biography